Why Is Change In Churches So Hard, Even When Survival Depends On It?

Have You Ever Wondered. . . ?

Why is change in churches so hard, even when survival depends on it?

If the environment around you is changing, it goes without saying that you should adjust accordingly so your organization can continue to thrive and grow, right? After all, if you are not able to pivot with environmental changes, your congregation risks stagnation—or even worse, extinction. So, if adaptability is such an obvious response, why do so few organizations succeed in their attempts at change? Or, why do so few organizations bother to start a change initiative to keep up with the changing times?

When faced with a situation that requires modification to existing systems or organizational culture, saying that “change is hard” and walking away is its own form of resistance. It is easy to hide behind how difficult the work of change is: “We don't have the resources,” “We don't have the energy,” or “We’ve tried that before” are familiar phrases in the language of resistance. If we fundamentally believe change is hard or even impossible, it provides us with a psychologically comfortable space where we can remain entrenched in patterns that may have outlived their usefulness.

Change Is Hard

Kurt Lewin’s Model of Force Field Analysis suggests that when the forces promoting change equal the forces promoting the status quo, organizations get stuck. So, what is necessary to get unstuck? One solution is to consider what each “force” has to lose or gain as a result of the proposed change.

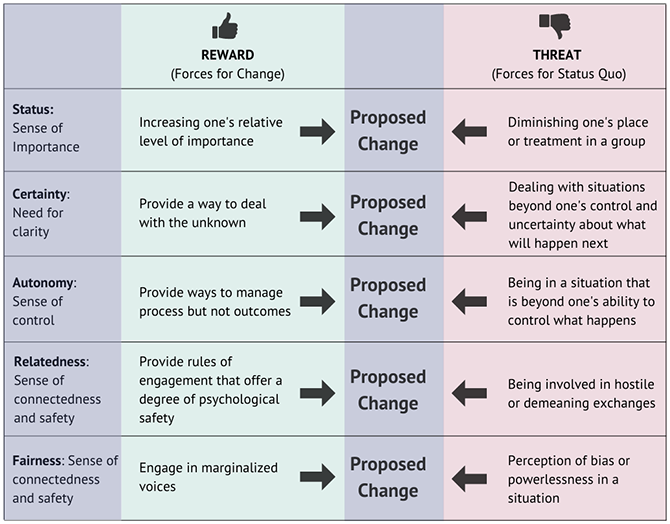

Dr. David Rock, a scholar of neuro leadership developed the SCARF® Model. SCARF Is an acronym for Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Fairness. The balance between psychological threats and psychological rewards heavily influences human behavior and group dynamics. For example, if one group within the organization feels that their status will be diminished if another group gains more power or status, then the force between change and the status quo will remain constant. In other words, the organization is static. However, if organizations can identify which individuals and groups feel threatened and rewarded by change, the potential exists to disrupt the dynamic perpetuating the resistance.

What Can Congregations Do?

So, if resistance to change is such a heavily nuanced and deeply embedded, unconscious mindset, what can congregations organizations do to disrupt the balance between the threats and rewards of potential change?

Disruption can be externally or internally influenced. The death of George Floyd was an external event that exposed one aspect of systemic racism to the world. The 8.34-minute video spurred millions into action and disrupted the status quo. External disruption is often unexpected and forces change in organizations. Internal disruption is more subtle, and to be effective, it must be intentional. In congregations, disruption often begins with a “champion”— a group of individuals who are called to advance a cause. To gain traction within the organization, though, “disruption” involves a planned approach to developing a culture of humility among members and engaging in courageous conversations about what each party finds threatening. Without some degree of awareness of other people’s motivations and fears, people tend to respond in a way that is aligned with their own beliefs, which only reinforces the tension between change and the status quo. And . . . this is where the work of getting unstuck begins.

Irrespective of the change your organization seeks or how many resources you have invested in developing missions and vision statements, it is the “perfectly imperfect” human beings who will implement them. Taking the additional step to explore how the change will impact the status, control, autonomy, relatedness, and fairness of each party is where the work of getting unstuck begins. Inclusion of all voices in conversations is the disrupting force that will ease the tension between the forces for change and the forces resistant to it.